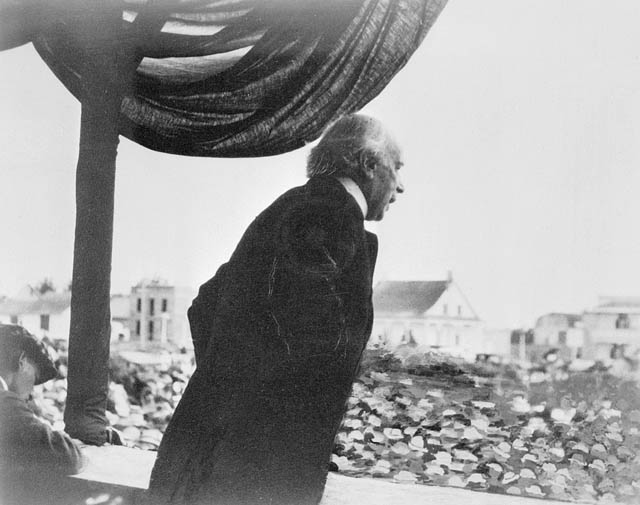

En tant que premier francophone premier ministre, Wilfrid Laurier travaille sans relâche à renforcer et à unifier le pays naissant et à bâtir des ponts entre ses citoyens anglophones et francophones, et ce, en dépit des réactions de mauvaise volonté que cela déclenche chez ses compatriotes québécois. L’unité et la fraternité sont les idéaux qui gouvernent sa vie, comme il le déclarera à un groupe de jeunes Canadiens le 11 octobre 1916, des valeurs que Jack Layton lui empruntera à la fin de son existence.

(Voir aussi La voie ensoleillée: les discours de sir Wilfrid Laurier.)

Faith is better than Doubt, Love is better than Hate: London, Ontario, 11 October 1916

Perhaps the occasion is not inappropriate that I should endeavour to set forth once again the traditions and hope and the ideals which have come to us from a long line of strong and patriotic men and which it has been my lot to endeavour to apply. Many questions have had to be solved during the last forty years and we have to apply their lesson to the conditions in which Canada and the Empire find themselves.

"I shall remind you that already many problems rise before you: problems of race division, problems of creed difference, problems of economic conflict, problems of national duty and national aspiration. Let me tell you that for the solution of these problems you have a safe guide, an unfailing light if you remember that faith is better than doubt and love is better than hate."

I need not tell you that we meet under the shadow of a terrible war which for the past two years has been desolating Europe and engrossing the attention of the civilized world. Neither would it be amiss if once more I recall that this is a war for civilization. If there be anyone in this audience, or elsewhere who may be of the opinion that this has been said too often that it might be left unsaid, I beg to dissent. It must be repeated and again, repeated so as to convince once more one and all in this country that the cause is worthy of every sacrifice. (Cheers)

And so saying I abate not a jot of my lifelong profession, reiterated in the House of Commons and upon many a platform of the country, that I am a pacifist. I have always been against militarism and I see no reason why I should be on the contrary. I see many reasons why I should not change, but still stand true to the professions of my whole life. But it has been clear to all and the pacifists: to the Radicals of England; to the Labour Party of England; to the Radicals, nay to all classes in France: to the Radicals of Italy, that in face of the avowed intention of Germany to dominate the world, in face of their blatant assumptions and complacent belief in being the “superman”; in face of their brutal assertions that force and force alone was the only law – it was clear, I say, to all pacifists that nothing would avail but such a victory as would crush forever from the minds of their German authorities the belief in atrocious theories and monstrous doctrines. (Cheers)

Hence it was that when war broke out those of us who were entrusted with the confidence of the Liberals of our country had no intention in declaring that it was the duty of Canada to assist to the full extent of her power the mother country in her supreme task of maintaining civilization by resort to arms. In this conviction we acted together as members of the party and pledged to support all war measures. It was no time for more party strife. Yet, occasionally – yes, more than once – we were confronted by measures brought forward by the Government so vicious in principle, so grievous in effect, that we could not be true to those we represent and ourselves if we permitted them to pass without taking the position of irreducible objection. . . .

We expected and hoped that the Government would realize the new conditions created by the war and would set itself with earnestness and consideration to the great tasks before it. But in this we, and then the people of Canada, have been to a large extent disappointed. (Hear, Hear)

It became the bounden duty of the Government in view of the heavy calls for military expenditures and the serious sacrifices which confronted the people of Canada to reduce all civil expenditure and strike off every item that could be dispensed with without impairing the national service. Was this done? Alas no. The fact is expenditure has been growing and growing and growing – going on as merrily as in the piping times of peace. . . .

I do not question at all the sincerity of the charge of Sir George Foster. He was sincere at the time. I have no doubt but his confession was not accompanied with repentance and determination to do better. He wanted to do better. His confession resulted almost in these words: “Let us agree on this – both sides – that hereafter patronage shall be eliminated.” (Laughter)

Hereafter – baneful word. This word “hereafter” – why not immediately? Why not unconditionally? Why wait until tomorrow. Tomorrow, and tomorrow and tomorrow (Laughter) “Tomorrow usurps in this petty pace from today, to the last syllable of recorded time.”

Tomorrow went by and with tomorrow went by also the suggestion and resolution of Sir George Foster never to return again until the last syllable of recorded time of this Government, the present Government of which he is an ornament, but not one of the masters. (Applause)

If his patronage had been eliminated from the Budget of this year, from the estimates of this year, it would have made an appreciable reduction. The patronage was there – patronage is an ubiquitous, omnipresent, omnivorous rover, devouring anything, everything in which there is any public money. It has a voracious insatiable appetite. Patronage is a plague, and if ever there was a time to be done with it, it is this calamitous time in which we are now living, in which everybody should be determined to have the biggest possible economy, the greatest possible reduction in the burden of the people. (Applause)

In the estimates of this year there is no less a sum than twenty-six million dollars appropriated to the Public Works Department presided over by the Hon. Robert Rogers, whom I never knew to be a master or an example in economy. (Laughter, applause) Eight millions are appropriated to capital account eighteen million dollars, the largest amount is in public buildings, post offices, postal stations, armouries and drill halls in small towns and smaller villages for which there is no necessity now, and there may be no necessity hereafter.

In times of peace, when the revenues were affluent, this amount of expenditure might be justified, but in times of war what excuse can there be and what is the reason for these expenditures? The reason for these expenditures is the eternal question of patronage, and if these items are still to be found this year in the estimates it is because removing them would offend many influential patrons in one of these towns or villages who has a lot to sell for which he can find no purchaser, but who is put in good humour with the hope that someday a benevolent Government will relieve him of this unprofitable piece of property. Is this indictment too strong in this strenuous time in which we are living? The indictment is more than justified. Sir, we want to win this war. And we shall and will. (Cheers)

Let us look at the situation as it is. Very strenuous times are opening before us, and it becomes necessary that the strictest possible economy would be applied to the public service. Why these expenditures? When we challenged the Government do you know the answer they gave? It was that they had no intention of spending the money. If they had no special intention of spending it, why ask Parliament to vote for it? If the Government did not have the courage to deny their friends, then do you think they will find more courage now that they have the money voted? The Government are bound to give us not only the precept but the example of economy. (Hear, hear)

This is my chief grievance against them. But there are many questions I might speak of. I might speak of the administration of the Department of Militia, but I will not do so on the present occasion as I shall have time to speak of it elsewhere. In the meanwhile let me again repeat that we must win this war. We have made every possible sacrifice and we are ready to do more if need be. We have loaded ourselves. We have sent our boys to the front where they have fought on the battlefields of Europe and on the soil of France with the same bravery which characterized their ancestors. They have shown that the blood that flows through their veins is still the same as that which was poured upon the soil of France.

But if we are ready to do this I ask if it not be a crime against the common interest of our country and Empire that there should not be one dollar expended than is absolutely necessary for the carrying on of the civil business of the country? Yet while our men are fighting at the front there are amongst us men consuming the midnight oil and spending a lot of printers’ ink in reconstituting the British Empire, but not along the old lines of British freedom, but upon the lines of German militarism! But it would be a sad day when we are engaged in a war the object of which is to save civilization if, as a result of this war, the victorious nations were to be saddled with militarism.

I ask you if anything has taken place in this war to lead any man to the conclusion that Britain has erred in her policy of anti-militarism or as maintaining her object the arts of peace, which have led her to where she is today? Is Britain in the wrong?

No sir, in the face of this there is no reason to believe that the policy of Britain in the past should be different from the policy in the future. There is an aphorism current that if you want peace you should prepare for war. I do not know the origins of the aphorism. But I assert that the experience of the world shows that the aphorism is apt to be fallacious. No, the experience of the world is that if you prepare for war, you will have war. Nothing better illustrates this than the policy of Prussian militarism.

Germany in this respect is only an enlarged Prussia. Prussia has dominated the German Empire and it is an admitted fact that Prussia impregnated Germany with that abominable lust of conquest which is now desolating the world. Prussia is the creature of the system of militarism. The first King of Prussia, Frederick William, invented the system. It has been extended again and again by his successors but it has not produced peace. On the contrary, more than one half of the wars which have desolated Europe in the last hundred and fifty years are due to Prussian militarism. . . .

Can you be surprised at this constant German aggression? No: if you educate men for war, if you prepare them for war and day after day teach them the doctrine of war then everyone from the Field Marshal to the humblest Corporal, during peace they sigh for the day when according to German conception, they will win glory and booty. In the first months of the present war we could hear the declarations of the German General Staff Officers and their exultation that in France they could fight for glory and in England there will be booty. The words may have been spoken or they may not have but they express the true spirit of the Prussian.

Even after the battle of Waterloo when Prussia and Britain were marching on Paris, the great Duke of Wellington maintained discipline in his army, but he wrote that the Prussians were simply thieves and robbers. (Cheers) Then when the old swashbuckler [Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von] Bluecher visited London and saw the rich city with its wealth piled up by British commerce, he, in true Prussian spirit, exclaimed: “What a city to sack!” (Laughter and cheers) This then is the spirit engendered by the system of militarism.

Against this history of Prussian arms and its organization and the glorification of war, let us look at a page of English history. The Kings of England, too, would have liked as the Kings of the European continent to have permanent armies, but the British people always looked upon permanent armies as an instrument of tyranny. They would not have them. The many devices of the Kings to get possession were baulked by Parliament. Today there is no law allowing a permanent army in Great Britain. . . . They have never had a standing army in the sense that European countries had them. The British conception supervened over all else, while the German conception led the people to look on war as a means to conquest and domination.

Between these two ideas there had to come a conflict and the conflict came. We are in it today. I ask you how shall it end. Sir, how it shall end is not now a question. Without haste, without undue exultation, with calm and confidence, with clenched fist and teeth, British subjects all over the world are determined that this conflict shall end in victory. (Loud cheers) But after victory comes the problem. That will be the question. What will follow? Shall we suppose that the old ideas, the old theories, which have made England and the British Empire what they are, shall it be supposed that the theories and the notions shall be thrown aside and a new military England and Empire be substituted for the old? Shall we have to say at the close of the war that old England is not the same?

For my part, British Liberal as I am – (cheers) – I do not know what the future may bring, but I have no hesitation in stating what my aspirations and hopes for British Liberalism may be. Let Britain remain true to the glorious past. (Cheers) Let her be in the future as she was in the past in the van of progress to that higher civilization which is now on trial, but which we hope to see, nay, are confident of seeing, emerge from the ordeal of blood and fire more glorious, more beneficent than ever. (Loud cheers)

I repeat, sir, this war has got to be fought to a finish. So it is that firmly, resolutely, we go on until victory is won. But then, let the better angels of our nature guide our course. There are many speculations now as to what should be our relations with Germany after the war. Sir, this is an idle question at the present time. It will depend on the extent of our victory. At all events if the victory be great or small, and I repeat that I think it ought to be great and thorough, it is not revenge that we are seeking. It is simple justice and freedom for the rest of Europe. (Cheers)

The German people are today under the ban of civilization on account of the atrocities which have been committed by the German army, on account of the innocent lives that are not sanctioned by war. For the victims of the Lusitania. For the babies killed by the Zeppelins. Yet for these atrocities the only persons to be held responsible are the German military authorities. And Germany will not only be answerable to history, but on the day of victory they will be charged before severe judges with the crimes they have committed not warranted by the law of war among the nations. But if the German authorities would be responsible it would be in the judgment of the British people whose motto has always been that of the old Roman “Fortibus, debellure parcere victis, superbus” which is to “fight the strong but to be merciful to the weak.”

Sir, I think we must hold the German authorities responsible. It would be unfair and unjust to hold all the German people to answer for such crimes. I believe, on the contrary, there is every reason to believe that when the new conditions will arise as must follow the war there will be an advance of democracy among the nations which compose the German Empire. There is every reason to believe that when the slaughter which has been going on for two years in Europe has come to an end the German people will realize that it is time the people, the common people as Abraham Lincoln used to say, who always in the end have to pay for the ambitious designs of despotism, should assert themselves. . . . There is every reason to believe that when the conflict is over the eyes of the German people will be opened and as a consequence despotism, feudalism, militarism shall be swept away by democracy, and democracy means peace, harmony, and good will amongst friends. (Applause)

And as for you my young friends, the Federation of Liberal Clubs, you who stand today on the threshold of life with a wide horizon open before you for a long career of usefulness to your native land, if you will permit me, after a long life, I shall remind you that already many problems rise before you: problems of race division, problems of creed difference, problems of economic conflict, problems of national duty and national aspiration. Let me tell you that for the solution of these problems you have a safe guide, an unfailing light if you remember that faith is better than doubt and love is better than hate. (Applause)

Banish doubt and hate from your life. Let your souls be ever open to the strong promptings of faith and the gentle influence of brotherly love. Be adamant against the haughty; be gentle and kind to the weak. Let your aim and your purpose in good report or in ill, in victory or in defeat, be so as to live, so to strive, so to serve as to do your part to raise the standard of life to higher and better spheres. (Sir Wilfrid resumed his seat amid a tornado of cheering.)

Partager sur Facebook

Partager sur Facebook Partager sur X

Partager sur X Partager par Email

Partager par Email Partager sur Google Classroom

Partager sur Google Classroom