Cet article a été initialement publié dans le magazine Macleans (13/03/1995)

A few minutes before Finance Minister Paul Martin was to deliver his budget speech in the House of Commons last week, he and Prime Minister Jean Chrétien met in Chrétien's second-floor office on Parliament Hill along with Martin's wife, Sheila, and Aline Chrétien. After a brief exchange of best wishes, the Prime Minister observed that his finance minister had forgotten the flower in his lapel that is customarily worn on budget day. No problem, suggested a Chrétien aide: the omission would symbolize the government's commitment to restraint. But, insisted Chrétien, "we must honor tradition." After a brief search, another aide found a bouquet of flowers on a nearby desk, snipped two red carnations, and gave one to each man to wear into the Commons. To break with the past, or honor it? To follow in the footsteps of previous finance ministers, or to boldly go where few of them have gone before? Almost from the day they were elected in October, 1993, those questions have bedevilled the Liberals in general, and Martin in particular. Along with another, most crucial one: how to remake an already-fragile Canada without fracturing it? Martin's response to that question - his budget of last week - provides the Liberals' first real attempt to deal with those issues since they came into power.

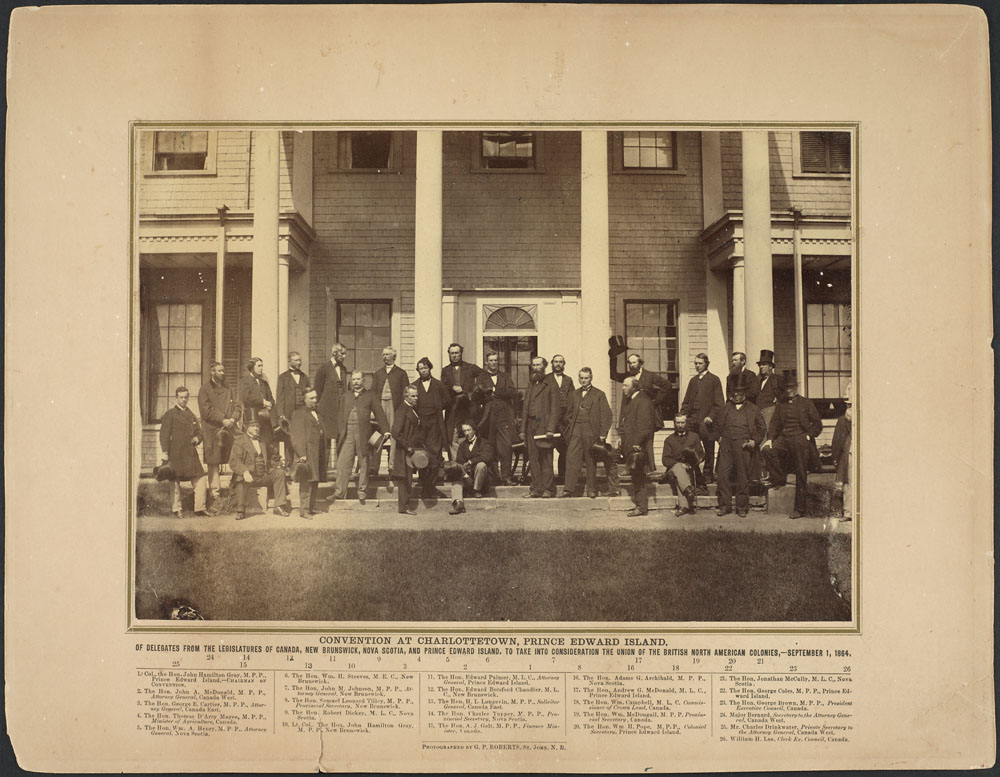

Behind those dilemmas lies a Liberal history of strong central government and national programs that extend almost all the way back to the year of Confederation. Martin's father, Paul Sr., after all, is regarded as the father of many of the government's most ambitious post-Second World War achievements. In turn, Paul Sr.'s hero, the party's legendary leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier said in a famous speech in 1877 that the policy of the Liberal party is to "protect, defend and extend" the "institutions by which we are governed." Laurier then added: "That is the policy of the Liberal party: it has no other."

But that was then: now, the Liberals, and the country, face more uncertain and less comfortable choices. Even before Martin tabled his budget last week, the Liberals were confronting grumbling provincial governments, a tax-choked populace and a road of foreign-owned debt that extends all the way around the world, with stops at the major money markets in Tokyo, London and New York City. Forty-six per cent of the federal government's $546-billion debt - which climbs at the rate of $85,000 per minute - is in foreign hands. Now, the task of Canada's politicians is not only, as Laurier said in the same speech, to keep Canadians "free and happy," but to ensure that those foreign investors feel the same way when they look at how the government is handling its finances.

Serving two disparate masters - the voters and the debt holders - is a virtual guarantee of offering both pleasure and pain. For now, the pain belongs mostly to the 45,000 federal civil servants who will lose their jobs over the next three years because of government cutbacks, along with the unemployed, welfare recipients and old age pensioners who are all likely to see cuts in their benefits in future. Some other losers include members of the arts and culture community; the Prairie provinces, where grain subsidies have been cut by $560 billion; and Ontario and Quebec, whose leaders quickly vied with each other to see which province could feel collectively more humiliated, downtrodden and picked-upon by the federal measures.

And it is almost certain that there will be other tough measures to come over the next year in areas not mentioned in the budget. Although it sets the broad course of the government's actions in the near future, Martin told Maclean's, "that does not mean that there won't be new things that aren't mentioned in that budget that aren't going to be improved on, or revised."

The pleasure, not surprisingly, was most evident abroad, where international moneylenders reacted to the tough measures with satisfaction that translated into a slight rise in the value of the Canadian dollar - which ended the week at 71.09 cents (U.S.) - and a slight fall in interest rates. More surprising, that sense that Martin had done his job well was also evident at home. A poll by the Angus Reid Group indicated that two out of three respondents approved of the budget, while the government's support actually increased five points - from 58 per cent to 63 per cent.

One reason for that satisfaction is that many Canadians were delighted to have been spared more direct hardship, such as an increase in personal income taxes. The absence of such an increase was enough to leave stillborn predictions of a full-blown taxpayers' revolt. Another reason is that, following the near-collapse of the New Democratic Party on the federal scene, the social-democratic movement in Canada is now largely irrelevant. The only substantive criticism of the budget nationally came from the Reform party - which called the budget "cowardly" because it did not contain even tougher measures. That made it easier for the Liberals, even as they presented the toughest budget of any federal government in recent history, to present themselves as kinder, gentler cost-cutters.

Another factor is that the full impact of the budget will only become evident on a gradual scale over the next three years. It will take that long, for example, for the government to buy out or offer early retirement to 45,000 employees, and for the planned $25 billion in spending cuts to take full effect. Similarly, Ottawa will cut 10 per cent out of the $15.3 billion spent annually on unemployment insurance, but it has not yet said whether that will be by tightening the conditions for eligibility, shortening the period of time for collecting benefits or reducing the size of benefits. Over time, welfare programs, which are run by the provinces, will inevitably be reduced because the federal government is also cutting the amount of money it gives the provinces to help finance the program. It is not yet clear what formula Ottawa will use to apportion the money it gives the provinces. But it is almost certain that whatever formula is used will result in a more uneven, patchwork system, with each province designing its own programs. Similarly, as Chrétien hinted strongly in a cbc Radio interview, the National Health Act - which oversees the medicare systems offered by each province - could be rewritten to eliminate guarantees of coverage for a number of medical services that now are offered for free.

Even among Liberals, enthusiasm is, at best, muted for many of the steps to be taken. A few MPs, such as Quebec's Warren Allmand and Newfoundland's George Baker, were openly critical of the budget's emphasis on cost-cutting. Martin himself conceded that one of the most painful steps was cutting the civil service. By contrast, when Brian Mulroney ran for office in 1984, he was almost gleeful in promising to deal with civil servants by giving them "pink slips and running shoes." But, said a sombre Martin, "if you ask if I enjoy cutting jobs, the answer is absolutely not." When he read his budget speech in the Commons, Liberal backbenchers were, for the most part, uncharacteristically silent, with none of the carefully orchestrated ovations that usually accompany such speeches. The Liberal party has long been criticized for favoring pragmatism over principles. The budget, reversing some of the promises in the Liberals' much-vaunted election campaign Red Book, lends support to that notion. It means that Chrétien, regarded as the most tradition-bound of recent prime ministers, is also leading some of the most radical changes of any of them. But for now, Canadians, like their Prime Minister, appear prepared to believe in the need to both honor their past - and break with it.

Maclean's March 13, 1995

Partager sur Facebook

Partager sur Facebook Partager sur X

Partager sur X Partager par Email

Partager par Email Partager sur Google Classroom

Partager sur Google Classroom